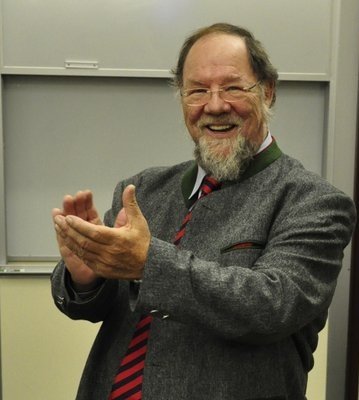

Professor Michael Czinkota: Biography, Academic Career and Professional Impact

- Posted: April 06, 2023

- Category: Writing 101

Michael Czinkota was an internationally renowned scholar, professor, and consultant who made significant contributions to the field of international business. He was born in Germany in 1951 and immigrated to the United States in 1956. He earned a Ph.D. in international business from the University of Birmingham in England and a Master's degree in international business from the University of California, Berkeley.

He was a prolific author and researcher who made significant contributions to the field of international business. Throughout his career, he published numerous books and academic articles on topics such as export promotion, global marketing, and trade policy, and his work has had a profound impact on the way that businesses and policymakers approach international markets.

One of Czinkota's most significant contributions to the field of international business was his research on global marketing. In his book, "International Marketing", Czinkota emphasized the importance of understanding cultural differences and adapting marketing strategies to local markets. He argued that businesses must develop a deep understanding of the values, beliefs, and customs of their target audience in order to effectively reach them. This insight has helped to shape the way that businesses approach international markets, and it has become a cornerstone of modern global marketing strategies.

Czinkota was also a leading expert on trade policy, and his research has influenced policymakers around the world. In his book, "Trade Policy and Economic Integration in the Middle East and North Africa", Czinkota explored the challenges and opportunities of trade liberalization in the Middle East and North Africa. He argued that trade liberalization could play a crucial role in promoting economic growth and development in the region, but that policymakers must also address the social and political challenges that come with economic integration. His insights into trade policy have helped to inform the policies of governments around the world, and his work continues to influence discussions on trade and globalization.

Another area where Czinkota made significant contributions was in promoting exports from developing countries. In his book, "Exporting: From Start to Finance", Czinkota emphasized the importance of exports for economic growth and development, particularly in developing countries. He provided practical advice on how businesses and governments could promote exports, from identifying potential markets to securing financing. His work in this area has helped to spur economic growth and development in many countries around the world, and it has been widely praised by policymakers and practitioners.

In addition to his academic work, Czinkota was a sought-after speaker and consultant, and he shared his expertise with corporations, government agencies, and academic institutions around the world. He was also deeply committed to mentoring and supporting students, and he played a crucial role in shaping the careers of many young scholars and practitioners.

Hire verified specialists to complete your "do my homework" requests with ease. Academized offers the best writers capable of writing the most complicated assignments and delivering them on time.

Writing a Biography Essay About Michael Czinkota

Writing a biography essay about Michael Czinkota requires gathering information about his life, achievements, and contributions. Here are the steps to follow:

-

Conduct research: Gather information about Michael Czinkota's life, including his early life, education, career, and personal life. You can use various sources, such as books, articles, interviews, and online resources.

-

Create an outline: Organize your information into an outline, with the introduction, body, and conclusion. In the introduction, introduce Michael Czinkota and provide some background information. In the body, discuss his achievements and contributions in detail, such as his academic work, publications, and consulting work. In the conclusion, summarize the main points and reflect on his legacy.

-

Write the first draft: Use the outline to write the first draft, focusing on the key information and ensuring that the essay flows logically.

-

Edit and revise: Review the first draft and make any necessary changes. Check for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors, and ensure that the essay is well-structured and coherent.

-

Add personal touch: Add your personal touch to the essay to make it unique and engaging. You can include anecdotes, quotes, or personal observations that highlight Michael Czinkota's personality, values, or impact.

-

Finalize the essay: After completing the revisions, finalize the essay by proofreading it and making sure that it meets the requirements, such as length and format.

Overall, writing a biography essay about Michael Czinkota requires thorough research, organization, and attention to detail. It is essential to highlight his achievements and contributions while providing insights into his personality and legacy.